Because the liver isn’t always the only thing bleeding, sometimes air is rushing in where it doesn’t belong.

The Trap of Focus

Right upper quadrant trauma has a way of tricking you.

All eyes go straight to the liver, that big, bruised, bleeding organ soaking up the attention like a sponge. The haemoperitoneum makes the priorities seem obvious.

Control the bleeding. Stop the bile. Pack the laceration.

But the RUQ is a crossroads, a place where the wrong trajectory means you’re treating the wrong problem first. We get so fixated on the liver that we forget another structure sits just a few centimetres above it. One thin layer of muscle that separates sterile abdomen from dirty lung.

The diaphragm.

Miss that injury, and the real trouble begins after you think you’ve won.

Mechanism Matters, So Listen Closely

Stab wound just under the ribs?

Gunshot entry in the mid-axillary line?

Exit wound suspiciously high?

If the track even threatens the diaphragm, assume it’s injured until proven otherwise.

Penetrating trauma doesn’t care about your anatomical boundaries.

Neither should your judgment.

The Sneaky Diaphragm Injury

Diaphragmatic trauma is the classic delayed complication maker.

Early on, it’s silent, no bleeding worth mentioning, no dramatic physiology to flag it. You’re busy saving a life. The diaphragm waits.

But days later…

- Abdominal pain that doesn’t fit

- Fever

- Shortness of breath

- A chest X-ray that suddenly has bowel where lung should be

A missed tear becomes a sucking hernia.

Gas, gastric acid, and gut bacteria wander north, and the chest cavity, that once pristine space, becomes septic chaos.

I’ve seen it.

Once.

Never again if I can help it.

The Rule is Simple: You Must Look

If you’re already in the abdomen, inspect the diaphragm directly.

Not a glance. Not a passing thought.

Expose. Visualize. Palpate if you must.

Especially posteriorly, the tears love to hide back there.

Not opening the abdomen? Laparoscopy or thoracoscopy are your friends.

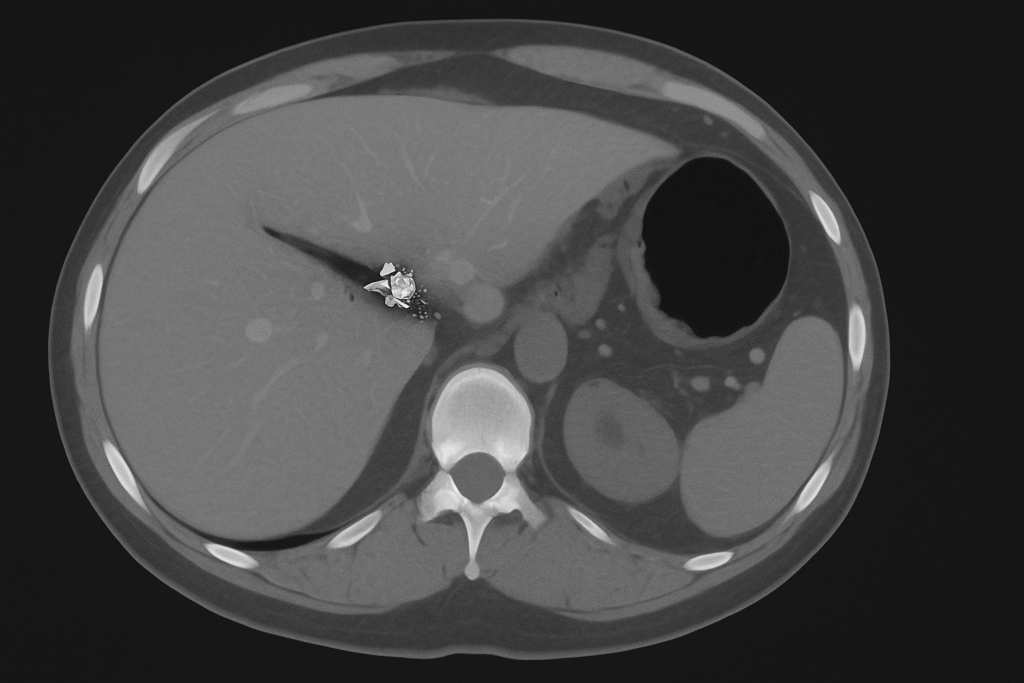

CT can lie. Air tracking can be subtle.

The only real exclusion is a real look.

If you think it’s fine, you’re guessing.

If you see it’s fine, you’re certain.

Repair: Quick, Solid, No Ego

Small tears? Primary repair with interrupted non-absorbable sutures.

Big ones? Same principle, just more patience.

Right-sided injuries used to be called “self-sealing” because of the liver’s presence.

That’s surgical folklore.

Right side or left side, a hole is a hole. Repair them all.

Because it’s not just herniation you’re preventing.

You’re maintaining the only barrier between gut bacteria and a lung that doesn’t deserve that invasion.

Don’t Forget Everything Else Nearby

RUQ penetrating trauma is rarely polite.

It slices through neighbourhoods:

- Liver

- Bile ducts

- Hepatic arteries and portal vein branches

- Colon (hepatic flexure)

- Duodenum

- Kidney

- Adrenal gland

Each one has a different way of punishing you if you overlook it.

But the diaphragm is the quietest about its revenge.

Damage Control Applies Here Too

If the patient’s crashing, you know the drill:

- Pack liver

- Control bleeding and bile

- Temporise the abdomen

But even in damage control, if you can’t fully exclude a diaphragmatic defect, drain the chest.

Better a prophylactic chest tube than a tension pneumothorax at 3 a.m.

Come back when physiology forgives you and repair what you know might be there.

Experience Makes the Rule

Every trauma surgeon who has done this long enough has one missed diaphragm injury story.

One is enough.

After that, the habit is burned into you like a scar:

Always check the diaphragm.

Above the costal margin is chest until proven otherwise.

Below the nipple line is abdomen until proven otherwise.

In between is your problem, and it better become your priority.

And From the Patient’s Side

Because while we debate entry zones and wound trajectories, they’re the ones lying there, breath shallow, ribs sore, wondering why a stab wound to the belly can suddenly steal their ability to breathe.

They don’t know what the diaphragm is. They just know something’s wrong, and they want their lungs back.

For us, it’s a missed tear.

For them, it’s the difference between waking up, and never waking up again.

That’s why we must not forget the importance of the secondary survey and the big role playing in the medical trauma field.

“How many trauma cases have been documented in which paramedics or TCCC teams focused primarily on the MARCH algorithm or the primary survey, without allocating sufficient time for a secondary survey? In many of these cases, the providers treated only the visible external injuries and unintentionally overlooked deeper, non-visible injuries such as internal bleeding.”

Professor Khan if you can talk about this I will be happy