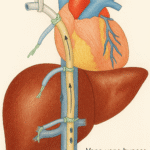

A reflection on those maddening post-trauma bile leaks, the slow, sticky reminders that the liver heals on its own time, not ours.

You Know the Look

That moment when you check the drain output post-liver injury, expecting it to lighten, and instead it’s still there, the unmistakable green-gold hue of bile.

Not serous, not sanguineous. Bile. Day after day.

You sigh, maybe curse softly. The patient’s otherwise fine, vitals steady, afebrile, tolerating oral intake. But that bile output mocks you from the drain bulb like a slow-dripping reminder that the liver always gets the final say.

We’ve all been there. And yet, every time, it pokes at that uneasy part of a surgeon’s brain that equates any leak with failure.

Why It Happens (Even When You Swear You Did Everything Right)

Blunt liver injuries are sneaky. You patch up the lacerations, pack judiciously, respect the hilum, and the patient stabilizes. You think you’re through the storm. Then, three days later, the drain turns chartreuse.

It’s not a technical flaw nine times out of ten. It’s physiology.

Those small intrahepatic bile radicals, the ones you can’t see and couldn’t possibly suture, get disrupted when the parenchyma’s been shredded. The bigger ducts are usually intact, but the little ones ooze like leaky pipes behind drywall.

And bile, unlike blood, doesn’t clot. It just seeps. Quietly. Persistently.

You can’t cauterize it, you can’t compress it, and you can’t rush it. The liver decides when it’s done leaking, not you.

The Trap: Doing Too Much, Too Soon

The first instinct, especially in younger surgeons, is to do something. Order imaging. Call interventional radiology. Schedule an ERCP.

But here’s the thing, most bile leaks close on their own, given time, drainage, and patience.

ERCP stenting is elegant, sure, but it’s often unnecessary unless the drain output’s high-volume or persistent beyond 10–14 days.

What kills patients isn’t the leak itself, it’s the complications of impatience: undrained bilomas, premature drain removal, or infection from fiddling too early.

If the patient’s afebrile, labs stable, no peritonitis, leave it alone. Watch the trend, not the colour.

What Matters More Than Output

Here’s what I actually care about in these cases:

- Is the patient septic? No? Good.

- Is the drain doing its job? Fluid’s clear, no collections on imaging? Perfect.

- Is the volume trending down? Even if slowly, you’re winning.

I’ll take a steady 50 mL/day of clean bile for a week over a sudden “zero” after the drain’s been pulled too soon.

Because nothing ruins your day like reopening a biloma that could’ve quietly dried up in another 48 hours.

When to Step In

There are only a few situations where I act:

- Output > 200 mL/day beyond 7–10 days, that’s usually a ductal injury that needs decompression.

- Fever or leukocytosis despite drainage, suspect undrained collection or infection.

- Persistent high bilirubin in the drain after two weeks, likely a major duct leak.

- No improvement at all and the patient’s starting to smell like bile every time you round.

That’s when ERCP earns its keep. The stent gives bile a path of least resistance, the leak dries, and everyone looks smarter than they are.

But the rest? Leave it be. The liver heals. It always does, slowly, stubbornly, but thoroughly.

The Psychological Bit: Leaks Feel Personal

There’s a strange kind of shame that comes with bile leaks.

They’re not catastrophic, nobody’s coding, the ICU’s calm, but they gnaw at you. The daily reminder that your operation wasn’t “clean,” that something’s still leaking.

I used to take it personally. Now I see it differently.

It’s not failure, it’s biology on its own clock. The same way seromas form, or pancreatic edges ooze, or spleens sulk after trauma. The body’s just working through the chaos.

We patch, we drain, we wait. That’s the job.

Old Habits Die Hard

Some still believe early drain removal is a sign of surgical confidence. I disagree.

A well-placed, low-output drain in a healing liver is not a crutch, it’s insurance.

Pulling it too early to look “decisive” is a rookie mistake. You can’t aspirate bile through bravado.

If the patient’s eating, ambulating, and smiling, let the drain sit until the output dries to almost nothing. Half the time it stops on day nine when you swore it’d go on forever.

The other half, it’ll stop on day fifteen when you’re tired of checking.

Either way, time wins.

In the End, the Liver Teaches You Patience

Every bile leak, big or small, is a reminder that trauma surgery isn’t about perfection. It’s about persistence.

You can’t muscle through physiology. You just manage it, intelligently, humbly, and with a bit of humour.

Because when that bile finally stops, and you pull the drain, and the patient walks out smiling…

You’ll remember it wasn’t your stitch that healed them. It was the liver doing what it’s done for millennia, sealing itself up, one tiny duct at a time.

And if that’s not humbling, I don’t know what is.

And while we’re watching numbers and charting volumes, they’re lying there, listening to the slow gurgle of that drain beside them, wondering if it means they’re healing or breaking.

They trace the tubing with their eyes, measure time by the sound of it emptying, and hope that each day’s colour means something better. They don’t see physiology or parenchyma; they just feel tired, fragile, grateful.

So while we wait for the leak to stop, remember for us, it’s another lesson in patience.

For them, it’s life slowly finding its way back.