In the chaos of a shattered liver and a bleeding retrohepatic vena cava, the atrio-caval shunt has always been the stuff of legend, but legends, as it turns out, don’t save lives.

Let’s Be Honest, We’ve All Heard the Tale

Every trauma surgeon, at some point early in their training, gets that same grim bedtime story:

A patient rolls in with a mangled liver, blood pouring from everywhere, pressure in the 40s, anesthesia shouting, and someone, usually the most senior person in the room, says it like a battle cry:

“We need an atrio-caval shunt!”

Cue the hushed awe. The residents freeze. The scrub nurse blinks twice. You can almost hear the background music swell.

Except… reality doesn’t play that tune.

In truth, the atrio-caval shunt is one of trauma surgery’s most romanticised ghosts, the kind of thing that sounds daring in a lecture or a textbook, but in the trenches, it’s an act of desperation masquerading as innovation.

The Anatomy Doesn’t Care About Your Confidence

Let’s paint the scene.

Retrohepatic vena cava injury. The kind that makes the OR go quiet for half a second before everyone starts moving faster than they can think.

Blood’s filling the field. You can’t see a thing. The Pringle’s on, but it’s doing nothing. The anaesthetist’s voice cracks slightly when they call out, “We’re losing pressure!”

So you try to control inflow and outflow: clamp the suprahepatic and infrahepatic cava, isolate the hepatic veins, classic textbook choreography.

And then someone says it again: “Let’s do a atrio-caval shunt.”

Here’s the problem: by the time you’re even thinking that, the patient’s physiology is already gone. You’re not resuscitating them, you’re embalming them with technique.

The reality is brutal. The patients who actually survive those situations? They usually didn’t need a shunt. Their cava wasn’t fully shredded, or the injury was controllable with packing, finger pressure, or selective repair.

The “success stories” of the atrio-caval era are mostly cases that would have done fine without it.

The Myth of “Heroic Surgery”

There’s a seductive mythology in trauma surgery: that in the right hands, a bold move can turn the tide. And sure, sometimes that’s true. But the atrio-caval shunt isn’t one of those moves. It’s a manoeuvre that buys time for anatomy, not life for the patient.

Let’s face it, no human being in full haemorrhagic shock, with no venous return and no cardiac preload, is going to magically rebound because you inserted a bit of tubing between veins. It’s a physiological dead end.

I’ve watched it done. I’ve done it once myself, years ago, back when we thought “heroic” meant “effective.” It didn’t end heroically.

The truth? If your patient can survive long enough for you to actually set up and insert an atrio-caval shunt, they probably didn’t need it in the first place.

Meanwhile, in the Real World: Veno-Veno Bypass Actually Works

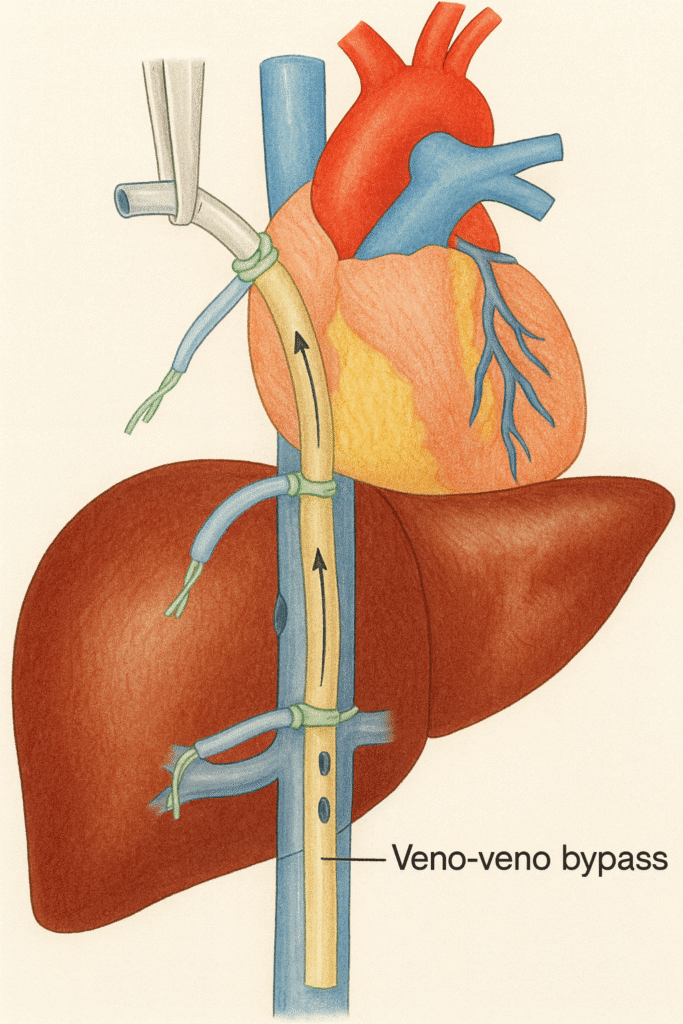

Now, compare that with veno-veno bypass, a technique that doesn’t pretend to be magic, just solid physiology.

It’s elegant, really. Instead of wrestling the liver like it’s a wild animal, you give the blood another route home. Drain from the femoral system, return to the jugular or subclavian, maintain preload and systemic flow. You buy time, real, measurable time, to fix what’s broken.

When used early, before the spiral into irreversible shock, veno-veno bypass can make the difference between chaos and control.

It’s not glamorous. There’s no Hollywood soundtrack. It’s perfusion tubing, suction, and pragmatism. But it works.

And in trauma, that’s all that matters.

Why the Atrio-Caval Shunt Refuses to Die

You’d think, with decades of dismal outcomes, that we’d have buried the atrio-caval shunt long ago. But myths are stubborn things.

Part of it’s ego. Nobody wants to admit that their mentor’s “heroic save” was just survivorship bias.

Part of it’s nostalgia, the idea that we’ve lost some of the boldness of old-school surgery.

But here’s the thing: boldness without biology is just theatre.

We don’t need cowboys in the trauma bay; we need physiologists with scalpels.

The younger surgeons get it. They’ve grown up in the age of balanced resuscitation, endovascular tricks, and perfusion support. They’re not chasing the ghosts of 1980s case reports. They’re chasing survivable outcomes.

Real Talk: What Works and What Doesn’t

Let’s call it plain:

- Atrio-caval shunt? Technical flex, poor survival.

- Total vascular isolation of the liver? Occasionally, yes, but at enormous cost.

- Packing and staged damage control with IR follow-up? That saves lives.

- Early veno-veno bypass? That’s the unsung hero.

I’d rather have a perfusionist and a good anaesthetist than a dozen retractors and a shunt kit any day.

The Quiet Truth Behind the Myth

I sometimes think the atrio-caval shunt survives as a kind of surgical folklore because it captures something about us, our need to do something when everything’s falling apart. It’s the same impulse that makes us push another epi when we know the rhythm’s gone.

It’s human. It’s understandable. But it’s not good surgery.

Real heroism is restraint.

Real heroism is saying, “This patient doesn’t need a shunt, they need physiology.”

That’s not romantic. It doesn’t make for good stories. But it saves lives.

Final Thoughts

The atrio-caval shunt belongs in the museum of trauma surgery, next to the bullet forceps and the era of blind clamping. It’s a reminder of where we came from, not where we should be going.

Meanwhile, veno-veno bypass stands quietly in the corner, no fanfare, just results. It doesn’t need myth. It has math.

And if there’s one thing I’ve learned after decades in this business, it’s this:

In trauma, physiology always wins.

And while we argue technique and talk shunts and bypasses, somewhere there’s the person who was on that table, the one whose body became the battleground for all our decisions.

They’ll never know what was said, or how close they came to slipping away. They won’t remember the chaos, the clamps, or the seconds that felt like hours. But someone waiting outside will remember every one of those moments for the rest of their life.

So when you stand there, blood on your gloves and exhaustion in your bones, don’t forget, for us it’s another case, another night; for them, it’s the edge between being a memory and coming home.