Pain isn’t just anatomy. It’s history.

Every time someone grabs their abdomen and says, “It hurts here,” they’re not only showing you a symptom, but they’re also whispering secrets from their embryological past. The gut remembers where it came from, quite literally.

And that’s why two patients can both clutch their bellies, grimacing in identical agony, but one has a perforated ulcer and the other has renal colic. Their pain travels old, primitive roads laid down before they were even recognizably human.

Let’s peel those layers again, this time, with evolution and embryology on our side.

Skin, The Surface Signal

The skin is honest. It tells you exactly where it hurts because it’s somatically innervated, direct, mapped, and predictable.

Pain here is clean and localised. Think shingles again, T7 to T12 dermatomes wrapping around the torso, angry and unmistakable. That pain is the nervous system shouting in capital letters: “This dermatome is under siege!”

From an embryological standpoint, the skin’s sensory nerves arise from somatic mesoderm derivatives, precise segmental origins. That’s why the brain can pinpoint their distress so accurately.

Fat and Muscle, The Protective Layers

Just beneath the skin, the subcutaneous fat and muscle layers act as both armour and alarm.

Their pain also comes from somatic nerves (again, cleanly mapped), which is why you can localise a strained rectus abdominis or an abscess in the abdominal wall so well.

These structures develop from somitic mesoderm, the same origin that gives rise to skeletal muscle, dermis, and connective tissue. Their nerves, the ventral rami of spinal nerves, retain that tidy segmental arrangement. Hence, somatic pain from these layers never confuses the brain about “where.”

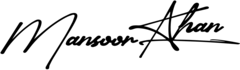

The Peritoneum, A Tale of Two Linings

Now things get interesting. The peritoneum is split into two kinds, embryologically and functionally:

- Parietal peritoneum arises from somatic mesoderm → innervated by somatic nerves → sharp, localised pain.

- Visceral peritoneum arises from splanchnic mesoderm → innervated by autonomic nerves → dull, poorly localised pain.

That’s the great divide. The parietal layer behaves like skin, honest, reactive, and precise. The visceral layer, though, is vague, dreamy, and impossible to interrogate.

It’s why early appendicitis starts as a dull, midline, visceral ache (from the midgut’s splanchnic nerves at T10) and later shifts to sharp right lower quadrant tenderness once the parietal peritoneum becomes inflamed.

Embryology explains that entire clinical story better than any CT scan ever could.

The Embryological Map of Visceral Pain

The gut tube in the embryo is divided into three segments:

| Region | Adult Derivatives | Spinal Segments | Pain Referred To |

| Foregut | Stomach, duodenum (up to D2), liver, gallbladder, pancreas | T5–T9 | Epigastric region |

| Midgut | Small intestine (distal duodenum onward), appendix, ascending & transverse colon | T10–T12 | Periumbilical region |

| Hindgut | Distal colon, rectum, bladder | L1–L2 | Suprapubic (hypogastric) region |

Each of these regions maintains its autonomic innervation from its embryonic origin. So, when the bowel distends or the gallbladder spasms, pain is perceived in the dermatome that shares that same spinal level, even though the actual problem is deep inside.

That’s why biliary colic feels epigastric, appendicitis starts periumbilical, and sigmoid pain drifts down to the suprapubic region. It’s not random. It’s foetal memory.

Shingles: The Embryo’s Revenge

We can’t ignore herpes zoster here; it’s the perfect bridge between dermatome and organ. Shingles respects the segmental embryological plan to the letter. The virus reawakens in the dorsal root ganglion of a specific spinal nerve, and bam, pain flares in the exact dermatome that nerve supplies.

So, when a patient complains of burning, wrapping pain over the abdomen, and you find nothing inside, remember, not every pain beneath the ribs is “in” the abdomen. Sometimes, it’s the nervous system replaying old embryological blueprints.

Why It Matters in Real Life

When a patient comes in saying, “my abdomen hurts,” your job is to figure out which layer, and which origin is talking.

- If it’s skin or muscle, it’s somatic: sharp, clear, reproducible with movement.

- If it’s deep and vague, think visceral, embryological pain from gut or organ stretching.

- If it’s sharp, localised, that’s the parietal peritoneum crying out.

- If it’s weirdly displaced, like shoulder pain for subdiaphragmatic irritation, you’ve met referred pain, another embryological echo.

Every pain has a birthplace; you just have to trace the nerve’s ancestral path back to the embryo that made it.

The Grand Moral

The abdomen is like an orchestra of nerves: some strings ancient, others newly tuned. When something goes wrong, the music changes, but to understand the tune, you must know where each instrument came from.

Embryology, far from being a dusty theory, is the Rosetta Stone of abdominal pain. It tells you why the gut can’t speak clearly, why the peritoneum shouts, and why the skin tattles first.

So next time a patient says, “It hurts here,” don’t just poke and prod, listen to the history written in their nerves.