A quiet organ that suddenly turns dramatic

You know those people who are calm and composed until, one day, they just explode?

That’s the gallbladder for you.

Most of the time it sits quietly under the liver, concentrating bile, minding its own business. Then, a tiny stone rolls into the cystic duct, and all hell breaks loose. Within hours, that gentle reservoir turns into a furious, inflamed sac that can make even the toughest patient whimper.

That, in essence, is acute cholecystitis.

The spark that lights the fire

The most common trigger (in over 90% of cases) is a gallstone blocking the cystic duct. The bile inside stagnates, pressure rises, the mucosa gets injured, and inflammation begins.

At first, it’s chemical irritation. But soon, bacteria join the party, typically E. coli, Klebsiella, Enterococcus, or Bacteroides. Now you have full-blown infection and inflammation of the gallbladder wall.

Occasionally, the same chaos can occur without stones, called acalculous cholecystitis, usually in the critically ill or postoperative patients. It’s rarer, but nastier.

The story patients tell

The patient’s narrative is almost always the same…

A dull, steady pain in the right upper quadrant, often following a fatty meal. It radiates to the right shoulder or scapula (hello, phrenic nerve). They look uncomfortable, sometimes febrile, occasionally clutching their side.

Ask them to breathe in while you press below the right costal margin. They’ll suddenly stop mid-inspiration, Murphy’s sign positive. It’s so reliable that, when you see it, you can almost hear the gallbladder shouting, “Enough already!”

Associated symptoms? Nausea, vomiting, fever, and anorexia. Jaundice can appear if inflammation causes secondary compression of the bile duct, the so-called Mirizzi’s syndrome, a favourite of examiners.

The inflammatory cascade, layer by layer

Pathologically, the gallbladder wall becomes thick, oedematous, and congested. As inflammation progresses, it can lead to:

- Empyema: pus-filled gallbladder

- Gangrene: necrosis of the wall

- Perforation: leaking bile into the peritoneum (peritonitis, the surgeon’s nightmare)

Over time, recurrent attacks can cause chronic cholecystitis, fibrosis, and adhesions to nearby structures like the duodenum or colon.

Investigations: looking inside the storm

- Blood tests:

- Raised WBCs

- Mild elevation of ALP or bilirubin (if inflammation compresses the ducts)

- Mildly deranged LFTs; markedly abnormal ones suggest choledocholithiasis.

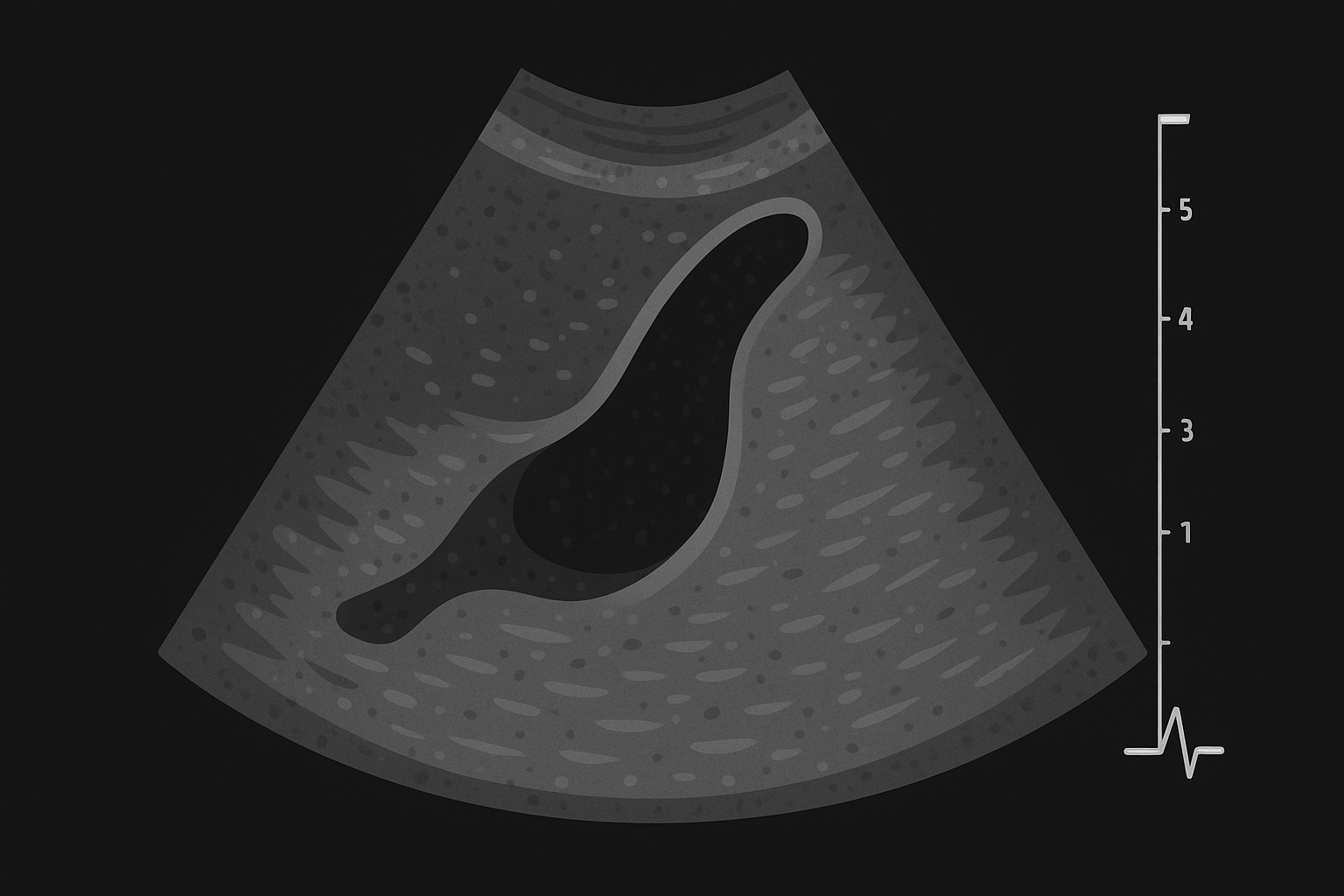

- Ultrasound:

The go-to investigation. Classic findings:- Gallstones

- Thickened gallbladder wall (>3 mm)

- Pericholecystic fluid

- “Sonographic Murphy’s sign” (pain when the probe touches the gallbladder)

- HIDA scan (hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid):

Used when ultrasound is inconclusive. The gallbladder won’t fill if the cystic duct is blocked.

CT is reserved for complications: gangrene, abscess, perforation.

Management: calm the fire, then remove the cause

Step one: stabilize.

- IV fluids

- Analgesia

- Broad-spectrum antibiotics (covering Gram-negative and anaerobes)

- Keep the patient NBM (nil by mouth)

Step two: definitive management.

The modern approach is early laparoscopic cholecystectomy, ideally within 72 hours of symptom onset. The old tradition of “cooling it down” first has largely faded, except in unstable or high-risk patients.

If surgery isn’t immediately feasible, a percutaneous cholecystostomy (radiologically guided drainage) can temporize until the patient recovers enough for definitive surgery.

Complications you’ll never forget

If untreated or delayed, acute cholecystitis can lead to:

- Empyema of the gallbladder

- Gangrene and perforation (into the peritoneum or adjacent organs)

- Pericholecystic abscess

- Cholecystoenteric fistula (and sometimes gallstone ileus)

- Sepsis and multi-organ failure in severe cases

A quick note on acalculous cholecystitis

A particularly cruel version seen in critically ill patients, burns, sepsis, trauma, or post-cardiac surgery. No stones, but plenty of inflammation, often due to bile stasis and ischemia.

Diagnosis can be tricky because symptoms are masked by the underlying illness, but ultrasound or HIDA scan helps.

Treatment is urgent antibiotics and cholecystostomy.

The surgeon’s takeaway

Acute cholecystitis is, in many ways, a surgical rite of passage. Every surgical trainee meets it, manages it, and, eventually, operates on it. It’s one of those conditions that teaches you clinical reasoning, anatomy, and decisiveness, all at once.

Remember:

- RUQ pain after a fatty meal? Think gallbladder.

- Murphy’s sign? Respect it.

- Don’t delay definitive management. Early surgery saves trouble later.

And finally, never underestimate how much mischief a 10 cm organ can cause when it’s angry.