There are two certainties in hepatic trauma: the liver bleeds like it means it, and physiology dies much faster than technique saves it. When the abdomen is a river and you can’t see the banks, the quickest, simplest manoeuvres buy you time. The Pringle manoeuvre is one. Temporary aortic control is another. Combined with disciplined mobilisation and effective packing, you convert chaos into repairable territory.

Below I’ll lay out a pragmatic sequence, indications, the how-to, timing limits, pitfalls, and when to call in alternatives like REBOA or IR. This isn’t a textbook chapter; it’s what I do when the monitors betray me and the anaesthetist is begging for temporizing moves.

Indications & mindset

- Indication: exsanguinating hepatic haemorrhage where exposure and definitive vascular repair are currently impossible. Think “damage control” physiology: acidosis, hypothermia, coagulopathy, or ongoing massive transfusion requirement.

- Objective: buy time, restore central blood pressure sufficiently to perfuse brain/heart while you control surgical bleeding. Not to perform definitive reconstruction in the same setting unless physiology allows.

- Team: announce pringle on, get the anaesthetist, scrub nurse, and circulating team aligned. Have blood and warming measures running. Communicate to IR early if embolization might be needed once you temporize.

The Pringle manoeuvre, how I do it (fast, reproducible)

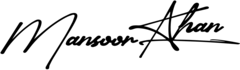

Goal: occlude inflow (portal vein + hepatic artery) by compressing hepatoduodenal ligament.

- Expose the hepatoduodenal ligament quickly. Use fingers to sweep the omentum inferiorly. Identify the free edge of the lesser omentum if necessary.

- Pass a tape or vascular clamp:

- Preferred: a soft vessel loop / taped right through the foramen of Winslow if you have time.

- Rapid option: use a large Kelly/trauma clamp to compress the hepatoduodenal ligament (works, but less controlled).

- Technique with a tape: place a right-angle clamp through the foramen of Winslow behind the porta, feed a wide tape, and bring both ends anterior. Pull snug and secure with a small clamp or tourniquet. Avoid strangulating the liver, aim for occlusion, not tissue crushing.

- Timing: Intermittent inflow occlusion is safer, aim for cycles of 10–15 minutes clamp with 5 minutes reperfusion, if possible. Total safe continuous clamp times vary by patient and physiology, in exsanguination you may exceed this, but be aware of ischaemic consequences.

- Effect: a well-placed Pringle often dramatically reduces bleeding from hepatic parenchyma and many arterial bleeds, it won’t control retrohepatic cava or hepatic vein injury.

Pitfalls:

- False comfort: it won’t stop bleeding from hepatic veins or a torn retrohepatic IVC.

- Misplaced tape (too anterior): no effect.

- Overly tight tape -> ischaemia of bile ducts; remember ischaemia risk if prolonged.

- Don’t rely on it as the only manoeuvre, combine with packing and other adjuncts.

Aortic cross-clamping to decrease IVC filling, options and pearls

Rationale: temporarily reduce distal arterial inflow and decrease venous return to the liver/IVC, lowering bleeding while you control the field. It’s high-stakes, use only when necessary and you have the team to support the physiologic hit.

Where to clamp:

- Infrarenal aortic cross-clamp (less physiologic hit than supracoeliac; easier via midline laparotomy if exposure allows). It reduces distal perfusion and can reduce IVC filling to a degree.

- Supracoeliac clamp (above the celiac axis) gives superior control of hepatic inflow but causes massive afterload and visceral ischaemia reserve for extreme situations and when you can tolerate the hemodynamic consequences.

- Alternative: REBOA (balloon occlusion in the aorta via femoral access), less invasive, quicker in experienced hands, and allows graded control. If you have a team that does REBOA, it’s often a better option than a hurried supracoeliac clamp.

Technique (open aortic clamp):

- Expose the aorta quickly: through midline laparotomy, retract small bowel to the left/right; for supracoeliac, divide the lesser omentum and gently mobilize the left lobe if needed. For infrarenal, expose just above bifurcation.

- Control iliac vessels if necessary for rapid clamping.

- Clamp application: use large vascular clamps (DeBakey aortic clamps). Apply swiftly, announce clamp time. Aim to minimize clamp-to-release interval.

- Monitoring: watch for massive hypertension above the clamp and ischaemia below; the anaesthetist must be ready for vasodilators when you release.

- Reperfusion planning: when you release, expect acidosis, hyperkalaemia, and hypotension, have blood, calcium, bicarbonate, and vasopressors ready.

Pitfalls & cautions:

- Aortic cross-clamp buys time but at physiologic cost, keep clamp time as short as possible.

- Supracoeliac clamps can cause profound cardiac strain and splanchnic ischaemia; don’t use lightly.

- REBOA, where available, often offers a better risk/benefit for brief control.

Mobilising the liver, exposure without chaos

Mobilisation matters. Done badly, you convert a controlled bleed into a free-for-all. Done well, it reveals the hilum and caval attachments you need to control.

Steps (right lobe focus):

- Divide falciform ligament close to the liver. Control any small bleeding from the ligamentum teres.

- Divide the right triangular and anterior coronary ligaments, sharp scissors with care. Stay on the peritoneal layer; avoid traction that tears capsule.

- Elevate right lobe medially and anteriorly to expose the bare area and retroperitoneal attachments. A liver retractor helps if space permits.

- Expose the retrohepatic IVC if needed by incising the posterior peritoneal reflection and gentle blunt dissection, only if you need to address hepatic vein/IVC injury and you have time/physiology to do so.

- Control small hepatic inflow branches encountered during mobilisation with clips or ties, don’t hesitate to ligate segmental vessels if they’re the source of bleeding.

Practical tips:

- Work from non-bleeding to bleeding areas, find a safe plane.

- Keep suction close; have an assistant dedicated to suction.

- Limit unnecessary traction on a friable liver, the capsule tears easily.

Packing the liver, the damage control bread-and-butter

Packing is not “lazy”, it’s lifesaving.

Principles: apply gentle, firm pressure to tamponade bleeding without strangulating tissue, and leave space for re-exploration.

Technique:

- Use large laparotomy sponges folded into packs (radiopaque). Two-handed placement: the assistant supports while you seat the pack under the liver edge or into the subphrenic space.

- Subhepatic packing: place packs between liver and abdominal wall and along Morrison’s pouch to compress the bleeding surface. For central lacerations, consider packing directly into the defect.

- Upper rib/diaphragm packs: packs in the subphrenic space help compress the dome. Avoid excessive pressure that causes ischaemia.

- Compression dressings and abdominal closure: after effective packing, do a temporary abdominal closure (Bogotá bag, VAC, or silo), do not close tightly. Mark packs and document number/position clearly.

- Timing: plan re-look within 24–48 hours once physiology corrected; leave packs in place until definitive control possible.

Pitfalls:

- Overpacking – compartment syndrome, increased intra-abdominal pressure, renal failure.

- Underpacking – ongoing bleed. Find the balance.

- Misplaced packs – missed source. Keep methodical placement and consistent documentation.

Combining the manoeuvres, an example sequence in exsanguination

- Rapid midline laparotomy. Scoop blood, apply suction.

- Immediate packing to slow diffuse bleeding and expose a field.

- Pringle manoeuvre immediately if hepatic parenchymal bleeding suspected. Reassess.

- If bleeding persists and IVC/hepatic vein suspected OR bleeding remains torrential: consider abdominal aortic control (infrarenal clamp).

- Mobilise right lobe only as much as necessary to inspect hilum/retrohepatic areas.

- Definitive haemostasis if physiology permits (suturing, vessel ligation, stapling). If not, pack and close temporarily.

- Transfer to ICU for resuscitation (balanced transfusion, warming, calcium), plan re-exploration or IR embolization as needed.

Post-procedure considerations & ICU handover

- Expect reperfusion injury on clamp release, anticipate hyperkalaemia, acidosis, and hypotension. Have calcium, insulin/dextrose, bicarbonate, and vasopressors ready.

- Monitor LFTs, lactate, and renal function closely.

- Remove packs at planned re-look: ideally within 24–48 hours once coagulopathy corrected.

- Liaise with IR early for possible angioembolization of arterial bleeders once the patient is stable.

- Document exactly: clamp times (Pringle total and intermittent), aortic clamp time, number/location of packs.

Techniques, refinements, and pearls from the trenches

- Pringle first, then think big. It’s fast and often dramatically helpful.

- Announce clamp times out loud. When it hits 15 minutes, consider reperfusion interval. Keep track, don’t rely on memory.

- Use wide tapes, not narrow ties. Wide tape distributes pressure and reduces focal ischaemia of the bile duct.

- Avoid blind dissection around hilum in coagulopathic patients, secure inflow control before you start fiddling.

- Temperature control is mandatory. Warm fluids, warming blankets, warmed OR environment if possible.

- Calcium administration during massive transfusion should be early and protocolized, citrate binds calcium and you will need it.

- If you find a retrohepatic IVC injury and physiology allows, get to veno-veno bypass / perfusion support or call for transplant/vascular help, otherwise pack and plan for staged repair or IR.

When NOT to do it

- Don’t attempt prolonged supracoeliac clamps in elderly cardiac patients or when you lack immediate ICU support.

- Don’t try definitive vascular reconstruction if the patient is coagulopathic, hypothermic, and acidotic, that’s a recipe for failure. Damage control first, reconstruction later.

Final thought, the patient’s side

For us it’s a sequence of clamps, tapes, and packs; for them it’s the night that nearly took everything.

They don’t remember the announcements of “Pringle on” or the aortic clamp. They only wake to breath, to pain, to a scar that tells the story we can recite in technical language.

So we do the ugly, urgent work with precision, and then we hand them back a life, imperfect, grateful, and profoundly human.