Because the liver doesn’t forget, it just waits for its moment to remind you that trauma doesn’t end when the bleeding stops.

The Morning After the Storm

You’ve stopped the bleeding. The packs are out. The drain’s clear, and the ICU team’s starting to look at you with cautious optimism. The liver’s holding, and you start to think, maybe this one’s through.

Then comes the fever. Low-grade at first. The CRP creeps up, the WCC follows, and the drain that was your silent ally suddenly turns cloudy, bilious, or both.

Welcome to the aftermath: bilomas, necrosis, and abscesses, the unholy trinity of delayed hepatic payback.

They’re not dramatic like a retrohepatic bleed. They’re slow, insidious, patient. The kind of complications that make you question whether you really won that first battle at all.

The Biloma: A Slow, Golden Betrayal

A biloma is a quiet injury with loud consequences.

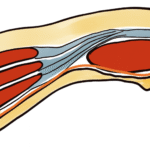

It starts with a small bile leak, maybe from a peripheral duct, maybe from a partial tear you never saw. The bile pools, sterile at first, warm and golden under the diaphragm.

Then it grows. Slowly. Painlessly. Until one morning, the patient’s right upper quadrant feels heavy, the LFTs start to twitch, and the ultrasound tech mutters the words you don’t want to hear:

“Collection, likely biloma.”

Small, contained bilomas can sometimes behave. They’ll reabsorb if the leak seals off and the drain’s well placed. But the larger ones, or those tucked deep beneath segments VI and VII, tend to become something else entirely.

That’s when you drain, image-guided, percutaneous, clean and calculated.

And if it’s persistent or reaccumulates? That’s your cue for ERCP and stenting. Give bile an easier way out than through the wound.

Because bile, like water, always finds the path of least resistance, and you’d better make sure that path isn’t into the peritoneum.

Hepatic Necrosis: The Liver’s Way of Saying “You Overdid It”

This one’s personal.

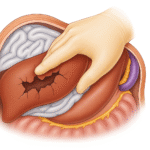

It’s what happens when devascularised segments that you thought might “declare themselves” decide to do it all at once.

A segmental infarct, a devitalised lobe, the price of vascular ligation, overzealous packing, or just bad luck.

At first, it’s subtle, rising inflammatory markers, dull RUQ pain, maybe a low-grade fever. Then the scan shows it: a wedge of non-enhancing parenchyma, mottled and angry.

If you’re lucky, it stays sterile. If not, it liquefies, turning into the perfect breeding ground for bacteria that didn’t get the memo that surgery was over.

When it happens, the game plan shifts:

- Drain early, before pus sets the rules.

- Antibiotics, broad at first, targeted once cultures talk back.

- Watch the borders. Expanding necrosis is a bad sign, it means sepsis is winning.

If the necrotic zone’s massive or segmental, and the patient’s fit enough, sometimes you have to go back, debride, deroof, or even resect.

But most times, it’s about patience, drains, and supportive care.

Because the liver, even half-dead, is still the best healer in the room.

The Hepatic Abscess: When Bile Meets Bacteria

You’ll smell it before you see it.

That sickly-sweet odour from a drain that’s turned murky brown-green. The CT confirms it: a gas-filled cavity in the liver, rim-enhancing, thick-walled, defiant.

This is where interventional radiology earns its reputation.

Percutaneous drainage, wide bore, low placement, repeat if needed.

Don’t be shy; these cavities collapse slowly.

Antibiotics alone won’t cut it. They’ll cool the fever but never kill the infection. The knife or the catheter finishes the job.

And whatever you do, resist the urge to pull the drain early.

Abscesses lie. They look quiet right before they come roaring back.

The Art of Waiting Without Worrying

The hardest part of managing post-traumatic liver collections isn’t the intervention, it’s the waiting.

Every day feels like purgatory. Drain outputs measured in millilitres, WBC trends scrutinized like stock prices, CTs done “just to be sure.”

You learn patience, and you learn humility.

Because these patients teach you that healing isn’t linear. It’s erratic, stubborn, and messy.

Sometimes, the bile stops on day five. Sometimes day twenty.

Sometimes the abscess closes quietly overnight. Sometimes it lingers, mocking your protocol.

And yet, most of them recover, not because of what you did, but because the liver simply decides to forgive you.

The Quiet Reckoning

Post-traumatic hepatic complications aren’t technical failures, they’re biology’s way of reminding you that trauma isn’t a single event, it’s a process.

You can stop the bleeding, but you can’t dictate the healing.

We like control. The liver teaches surrender.

And From the Other Side of the Drapes

And while we’re counting drains and debating timing, they’re the ones lying there, sore, jaundiced, tethered to tubing that gurgles every time they move.

They don’t know what a biloma is. They just know their body’s leaking something that shouldn’t be leaking.

They’re tired of scans and lines and the word “almost.”

They just want to be whole again.

So, as we round, measure, and document, maybe remember, for us, it’s post-trauma management.

For them, it’s learning to trust their body again, one quiet breath at a time.