Because even after you stop the bleeding, bile finds a way to remind you the job’s not over.

The Wound You Don’t See Right Away

Bleeding gets your attention. Bile doesn’t.

When a duct tears, it’s not chaos, it’s deceit. The patient stabilises, vitals look fine, and you start thinking about closure. But deep down, somewhere under the portal plate, something is quietly leaking.

And days later, when the abdomen’s tight, the drain turns green, and the labs show bilirubin creeping upward, that’s when the liver reminds you: you missed something small, but significant.

Extrahepatic biliary trauma is the injury that hides in plain sight. It’s not loud, not heroic, just relentlessly unforgiving.

Mechanisms and Mayhem

Blunt trauma, penetrating wounds, iatrogenic slips, the mechanism matters less than the realisation that by the time you find it, you’re already in trouble.

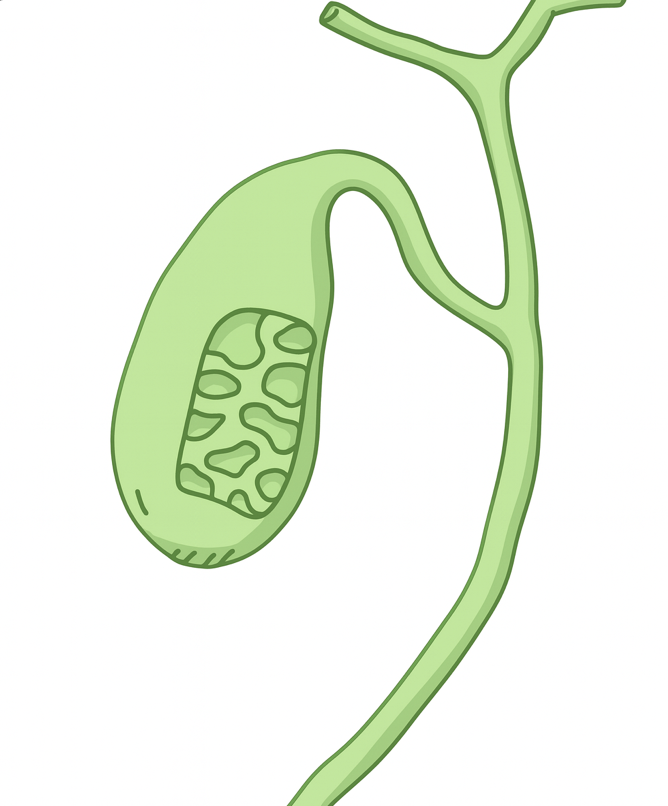

Sometimes it’s a partial tear of the common hepatic duct, a devitalized segment, or a clean transection that looks almost too neat.

Sometimes the gallbladder’s gone, sometimes it’s hanging by threads, and bile’s pooling in every recess like an accusation.

These injuries rarely travel alone; they come with liver lacerations, duodenal bruises, shattered hilum, or, if the gods are truly unkind, a vascular hit to match.

Recognition: The Slow Burn of Doubt

You’ll suspect it long before you see it.

Persistent bilious output from a drain that should’ve gone serous days ago.

A patient who’s afebrile but not quite right.

A CT that shows fluid where there shouldn’t be any, thick, yellow, and stubborn.

In trauma, the temptation is to label everything “liver ooze” or “minor bile leak.” Don’t.

If it’s persistent, high-volume, or worsening, it’s not minor. It’s your cue to look harder.

The Surgical Tightrope

The decision-making here is rarely binary.

Do too little, and you condemn them to sepsis and fistulae.

Do too much, and you risk an anastomosis on friable tissue that’ll unravel the moment you blink.

If the duct’s partially torn and you can patch it with a T-tube or primary repair over stent, good.

If it’s devitalised or transected, you’re heading for a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy — provided the field’s clean enough and the patient’s stable enough to handle it.

If not, damage control applies; external drainage, control contamination, come back when physiology forgives you.

Because in biliary trauma, impatience kills repairs.

When the Duct Is Lost

Every surgeon has a story, that one case where the anatomy made no sense.

A shattered hilum, bile mixing with blood, and no clear plane between duct and vein.

You grope through scar and ooze, praying for a recognisable structure, knowing one slip could turn salvage into catastrophe.

Sometimes, the right answer is to stop. Drain, stabilise, and live to fight another day.

The best surgeons aren’t the ones who finish; they’re the ones who know when to defer.

Endovascular and Endoscopic Lifelines

Modern trauma management isn’t always about open heroics.

If the patient’s stable and the leak is localised, ERCP with stenting can work miracles. It’s clean, controlled, and spares the duct another insult.

If the injury’s high and inaccessible, percutaneous transhepatic drains can bridge the gap, ugly but effective.

The goal isn’t perfection. It’s containment.

Because bile, when contained, heals. Bile, when free, infects. That’s the line we walk.

The Long Tail of Biliary Injury

The patient survives, leaves the ICU, the wound closes, but the story doesn’t end there.

Weeks later, the jaundice creeps back. The ultrasound shows ductal dilation. The bile ducts, insulted and scarred, start to narrow.

Stricture formation is the final insult, slow, silent, and maddening.

You can bypass, dilate, or stent, but you can’t undo fibrosis.

You can only manage it, one intervention at a time, one follow-up scan after another.

The Lesson That Never Fades

Biliary trauma teaches humility. It doesn’t roar like a ruptured aorta or demand speed like a shattered spleen. It whispers.

And those whispers, a rising bilirubin, a persistent leak, a drain that won’t clear, are the ones that test your judgment more than your skill.

It’s not about force. It’s about finesse, patience, and knowing when to let the liver, and the duct do the healing.

And From the Patient’s Side of the Drapes

And while we trace ducts and debate reconstructions, they’re the ones waking up with drains, tubes, and a scar that aches every time they breathe.

They don’t understand Roux-en-Ys or T-tubes. They just want to eat without pain, to sleep without a line tethering them to a bag.

For us, it’s anatomy and technique. For them, it’s the long road back to normal, to food that tastes right again, to nights without fear of yellow eyes or hospital lights.

So, the next time you chase a duct through a field of bile and blood, remember, for you, it’s a reconstruction, for them, it’s the difference between surviving and truly living again.