A funny thing about abdomens…

You’d be amazed at how many people, even those wearing pristine white coats, think of the abdomen as just a “belly.” A soft mound that rumbles when hungry and occasionally betrays you during ward rounds. But here’s the thing, it’s not just a container.

It’s an orchestra pit. Everything inside plays a part, sometimes out of tune, sometimes perfectly synchronised.

I once told a first-year, “The abdomen is like London, crowded, layered, a little confusing, but somehow, it works.” He looked at me blankly. I suppose anatomy isn’t the place for urban metaphors, but humour me.

The Boundaries: where the map begins

Every story needs its borders, and the abdomens are no exception. Up top, we’ve got the diaphragm, that gorgeous dome of muscle separating us from the chest’s commotion. It’s both a wall and a bridge, the ultimate multitasker.

Down below, the pelvic brim marks the official “here ends the abdomen, there begins the pelvis” line, though anatomically speaking, nature doesn’t really care about our tidy definitions.

Posteriorly? Ah, that’s where the unsung heroes live. The posterior abdominal wall is like backstage, unglamorous but absolutely vital. Psoas, quadratus lumborum, iliacus, and a few shy nerves weaving around, they keep you upright and, if you’ve ever spent twelve hours in theatre, painfully aware of their existence.

The lateral walls, meanwhile, are muscle-layered masterpieces: external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis, all stitched together by the rectus sheath and linea alba. They don’t just look good on fitness posters, they hold your life in. Literally.

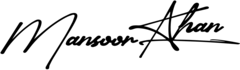

The Nine Regions: or “how to sound impressive during exams”

Draw two vertical lines from mid-clavicle to groin, then two horizontals, one at the costal margin, one at the iliac crest. Voilà, the abdomen becomes a 3×3 grid; nine fossae.

- Right hypochondrium (where the liver reigns supreme)

- Epigastric (where stomach and pancreas conspire)

- Left hypochondrium (where spleen hides like a bashful guest)

- Right lumbar (ascending colon, kidney lurking behind)

- Umbilical (loops of bowel arguing about space)

- Left lumbar (descending colon, kidney again doing its quiet duty)

- Right iliac (caecum and appendix, the troublemakers)

- Suprapubic (bladder, uterus if applicable, and small bowel loops)

- Left iliac (sigmoid colon’s curvy finale)

In real life, of course, nothing stays perfectly compartmentalised. The liver likes to wander left, the stomach overflows its zone, and the intestines are hopelessly nomadic. That’s anatomy’s version of teenage rebellion.

The Posterior Wall: where the real work happens

I’ve always had a soft spot for the back of the abdomen. Maybe it’s the quiet authority, aorta descending with purpose, inferior vena cava gliding upward like it owns the place. Behind them, the vertebral column stands sentry, a solid spine against the chaos in front.

Nestled here, too, are the kidneys, those unsung filters of life, retroperitoneal and dignified. They mind their own business until a stone decides to stage a protest. And the pancreas, slyly perched across the midline, half-hidden, half-essential.

Funny, isn’t it? The organs that make the least fuss are the ones that kill you quickest when ignored.

The Front Line: muscles, scars, and stories

When you open an abdomen, metaphorically or surgically, you’re entering a layered world. Skin, fat, fascia, muscle, peritoneum. Each tells a story. Old scars from appendicectomies, faded striae from pregnancies, surgical memories of another time. The anterior abdominal wall doesn’t forget.

Those muscles, rectus abdominis, obliques, transversus, they’re more than just anatomy trivia. They’re guardians of pressure, posture, and protection. Without them, a cough would send your insides looking for daylight.

The Organs: everyone’s got a role

The liver dominates the right upper quadrant like a benevolent dictator. The stomach sprawls lazily to the left, forever digesting and complaining. Spleen, fragile but noble, tucks itself under the ribs, just waiting to be “accidentally” injured in a trauma.

The small intestine coils in the middle like a restless python, endlessly absorbing, while the large intestine frames it neatly, or tries to. Down in the pelvis, the bladder and reproductive organs carry on their business with quiet dignity, except when they don’t.

And don’t forget the peritoneum, that shimmering membrane that lines, suspends, and cushions. It’s both a protector and, when inflamed, your worst enemy. (Ask anyone who’s dealt with peritonitis. You’ll get a grim nod.)

The Big Picture: not just a cavity, but a conversation

If you take one thing from this ramble, let it be this: the abdomen isn’t static. It moves, breathes, shifts with every heartbeat and hiccup. Boundaries blur, organs migrate slightly, and every patient’s interior landscape tells a different story.

When you examine a patient, don’t just palpate for tenderness; imagine what lies beneath. Picture the liver nudging the diaphragm, the aorta pulsing quietly at the back, the loops of bowel wriggling in perpetual motion.

Because anatomy, when learned well, isn’t memorised, it’s visualised, almost felt.

A Footnote (because every Professor loves one)

Oh, and one last thing. If you ever forget which kidney sits lower, it’s the right one. The liver’s to blame, as usual. And if you forget the boundaries of the abdomen during your viva, take a deep breath. The diaphragm will remind you where it starts.